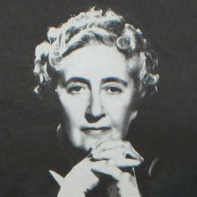

Agatha Christie

| Dame Agatha Christie, DBE | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller 15 September 1890 Torquay, Devon, England |

| Died | 12 January 1976 (aged 85) Wallingford, Oxfordshire, England |

| Pen name | Mary Westmacott |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Nationality | British |

| Genres | Murder mystery, Thriller, Crime fiction, Detective, Romances |

| Literary movement | Golden Age of Detective Fiction |

| Spouse(s) | Archibald Christie (1914–1928) Max Mallowan (1930–1976) |

|

Influences

|

|

|

|

|

| Signature | |

|

agathachristie.com |

|

Dame Agatha Christie, DBE (15 September 1890 –12 January 1976), was a British crime writer of novels, short stories and plays. She also wrote romances under the name Mary Westmacott, but is remembered for her 80 detective novels and her successful West End theatre plays. Her works, particularly those featuring detectives Hercule Poirot and Miss Jane Marple, have given her the title the 'Queen of Crime' and made her an important writer in the development of the genre.

Christie has been referred to by the Guinness Book of World Records as the best-selling writer of books of all time and the best-selling writer of any kind, along with William Shakespeare. Only the Bible is known to have outsold her collected sales of roughly four billion copies of novels.[1] UNESCO states that she is currently the most translated individual author in the world, with only the collective corporate works of Walt Disney Productions surpassing her.[2] Christie's books have been translated into at least 103 languages.[3]

Her stage play The Mousetrap holds the record for the longest initial run in the world: it opened at the Ambassadors Theatre in London on 25 November 1952 and as of 2010 is still running after more than 23,000 performances. In 1955, Christie was the first recipient of the Mystery Writers of America's highest honour, the Grand Master Award, and in the same year Witness for the Prosecution was given an Edgar Award by the MWA for Best Play. Most of her books and short stories have been filmed, some many times over (Murder on the Orient Express, Death on the Nile and 4.50 From Paddington for instance), and many have been adapted for television, radio, video games and comics.

In 1968, Booker Books, a subsidiary of the agri-industrial conglomerate Booker-McConnell, bought a 51 percent stake in Agatha Christie Limited, the private company that Christie had set up for tax purposes. Booker later increased its stake to 64 percent. In 1998, Booker sold its shares to Chorion, a company whose portfolio also includes the literary estates of Enid Blyton and Dennis Wheatley.[4]

In 2004, a 5,000-word story entitled The Incident of the Dog's Ball was found in the attic of the author's daughter. This story was the original version of the novel Dumb Witness. It was published in Britain in September 2009, alongside another newly discovered Poirot story called The Capture of the Cerberus, in John Curran's Agatha Christie's Secret Notebooks: Fifty Years Of Mysteries. On November 10, 2009, Reuters announced that The Incident of the Dog's Ball will be published by The Strand Magazine.[5]

Life and career

Early life and first marriage

Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller was born in Torquay, Devon, England, UK. Her mother, Clarissa Margaret Boehmer, was the daughter of a British army captain[6] but had been sent as a child to live with her own mother's sister, who was the second wife of a wealthy American. Eventually Margaret married her stepfather's son from his first marriage, Frederick Alvah Miller, an American stockbroker. Thus, the two women Agatha called "Grannie" were sisters. Despite her father's nationality as a "New Yorker" and her aunt's relation to the Pierpont Morgans, Agatha never claimed United States citizenship or connection.[7]

The Millers had two other children: Margaret Frary Miller (1879–1950), called Madge, who was eleven years Agatha's senior, and Louis Montant Miller (1880–1929), called Monty, ten years older than Agatha. Later, in her autobiography, Agatha would refer to her brother as "an amiable scapegrace of a brother".[8]

During the First World War, she worked at a hospital as a nurse; she liked the profession, calling it "one of the most rewarding professions that anyone can follow".[9] She later worked at a hospital pharmacy, a job that influenced her work, as many of the murders in her books are carried out with poison.

Despite a turbulent courtship, on Christmas Eve 1914 Agatha married Archibald Christie, an aviator in the Royal Flying Corps.[10] The couple had one daughter, Rosalind Hicks. They divorced in 1928, two years after Christie discovered her husband was having an affair. It was during this marriage that she published her first novel in 1920, The Mysterious Affair at Styles. In 1924, she published a collection of mystery and ghost stories entitled The Golden Ball.

Disappearance

In late 1926, Agatha's husband, Archie, revealed that he was in love with another woman, Nancy Neele, and wanted a divorce. On December 8, 1926, the couple quarrelled, and Archie Christie left their house Styles in Sunningdale, Berkshire, to spend the weekend with his mistress at Godalming, Surrey. That same evening Agatha disappeared from her home, leaving behind a letter for her secretary saying that she was going to Yorkshire. Her disappearance caused an outcry from the public, many of whom were admirers of Agatha Christie's novels. Despite a massive manhunt, there were no results until eleven days later.[11]

Eleven days after her disappearance, Christie was identified as a guest at the Swan Hydropathic Hotel (now the Old Swan Hotel[12]) in Harrogate, Yorkshire, where she was registered as 'Mrs Teresa Neele' from Cape Town. Christie gave no account of her disappearance. Although two doctors had diagnosed her as suffering from amnesia, opinion remains divided as to the reasons for her disappearance. One suggestion is that she had suffered a nervous breakdown brought about by a natural propensity for depression, exacerbated by her mother's death earlier that year and the discovery of her husband's infidelity. Public reaction at the time was largely negative, with many believing it was all just a publicity stunt while others speculated she was trying to make the police think her husband killed her as revenge for his affair.[13]

Second marriage and later life

In 1930, Christie married archaeologist Max Mallowan after joining him in an archaeological dig. Their marriage was especially happy in the early years and remained so until Christie's death in 1976.[14] In 1977, Mallowan married his longtime associate, Barbara Parker.[14]

Christie's travels with Mallowan contributed background to several of her novels set in the Middle East. Other novels (such as And Then There Were None) were set in and around Torquay, where she was born. Christie's 1934 novel Murder on the Orient Express was written in the Hotel Pera Palace in Istanbul, Turkey, the southern terminus of the railway. The hotel maintains Christie's room as a memorial to the author.[15] The Greenway Estate in Devon, acquired by the couple as a summer residence in 1938, is now in the care of the National Trust. Christie often stayed at Abney Hall in Cheshire, which was owned by her brother-in-law, James Watts. She based at least two of her stories on the hall: the short story The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding, which is in the story collection of the same name, and the novel After the Funeral. "Abney became Agatha's greatest inspiration for country-house life, with all the servants and grandeur which have been woven into her plots. The descriptions of the fictional Chimneys, Stoneygates, and other houses in her stories are mostly Abney in various forms."[16]

During the Second World War, Christie worked in the pharmacy at University College Hospital of University College, London, where she acquired a knowledge of poisons that she put to good use in her post-war crime novels. For example, the use of thallium as a poison was suggested to her by UCH Chief Pharmacist Harold Davis (later appointed Chief Pharmacist at the UK Ministry of Health), and in The Pale Horse, published in 1961, she employed it to dispatch a series of victims, the first clue to the murder method coming from the victims’ loss of hair. So accurate was her description of thallium poisoning that on at least one occasion it helped solve a case that was baffling doctors.[17]

To honour her many literary works, she was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 1956 New Year Honours.[18] The next year, she became the President of the Detection Club.[19] In the 1971 New Year Honours she was promoted Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire,[20] three years after her husband had been knighted for his archeological work in 1968.[21] They were one of the few married couples where both partners were honoured in their own right.

From 1971 to 1974, Christie's health began to fail; however, she continued to write. Recently, using experimental, computerised, textual tools of analysis, Canadian researchers have suggested that Christie may have begun to suffer from Alzheimer's disease or other dementia.[22][23][24][25][26] In 1975, sensing her increasing weakness, Christie signed over the rights of her most successful play, The Mousetrap, to her grandson.[14] Agatha Christie died on 12 January 1976 at age 85 from natural causes at her Winterbrook House in the north of Cholsey parish, adjoining Wallingford in Oxfordshire (formerly Berkshire). She is buried in the nearby churchyard of St Mary's, Cholsey.

Christie's only child, Rosalind Margaret Hicks, died, also aged 85, on 28 October 2004 from natural causes in Torbay, Devon.[27] Christie's grandson, Mathew Prichard, was heir to the copyright to some of his grandmother's literary work (including The Mousetrap) and is still associated with Agatha Christie Limited.

Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple

Agatha Christie's first novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles was published in 1920 and introduced the long-running character detective Hercule Poirot, who appeared in 33 of Christie's novels and 54 short stories.

Her other well known character, Miss Marple, was introduced in The Tuesday Night Club in 1927 (short story) and was based on women like Christie's grandmother and her "cronies".[28]

During the Second World War, Christie wrote two novels, Curtain and Sleeping Murder, intended as the last cases of these two great detectives, Hercule Poirot and Jane Marple, respectively. Both books were sealed in a bank vault for over thirty years and were released for publication by Christie only at the end of her life, when she realised that she could not write any more novels. These publications came on the heels of the success of the film version of Murder on the Orient Express in 1974.

Like Arthur Conan Doyle with Sherlock Holmes, Christie was to become increasingly tired of her detective Poirot. In fact, by the end of the 1930s, Christie confided to her diary that she was finding Poirot “insufferable," and by the 1960s she felt that he was "an ego-centric creep." However, unlike Conan Doyle, Christie resisted the temptation to kill her detective off while he was still popular. She saw herself as an entertainer whose job was to produce what the public liked, and the public liked Poirot.[29]

In contrast, Christie was fond of Miss Marple. However, it is interesting to note that the Belgian detective’s titles outnumber the Marple titles more than two to one. This is largely because Christie wrote numerous Poirot novels early in her career, while Murder at the Vicarage remained the sole Marple novel until the 1940s.

Christie never wrote a novel or short story featuring both Poirot and Miss Marple. In a recording, recently rediscovered and released in 2008, Christie revealed the reason for this: "Hercule Poirot, a complete egoist, would not like being taught his business or having suggestions made to him by an elderly spinster lady".[28]

Poirot is the only fictional character to have been given an obituary in The New York Times, following the publication of Curtain in 1975.

Following the great success of Curtain, Christie gave permission for the release of Sleeping Murder sometime in 1976 but died in January 1976 before the book could be released. This may explain some of the inconsistencies compared to the rest of the Marple series — for example, Colonel Arthur Bantry, husband of Miss Marple's friend Dolly, is still alive and well in Sleeping Murder despite the fact he is noted as having died in books published earlier. It may be that Christie simply did not have time to revise the manuscript before she died. Miss Marple fared better than Poirot, since after solving the mystery in Sleeping Murder she returns home to her regular life in St. Mary Mead.

On an edition of Desert Island Discs in 2007, Brian Aldiss claimed that Agatha Christie told him that she wrote her books up to the last chapter and then decided who the most unlikely suspect was. She would then go back and make the necessary changes to "frame" that person.[30] The evidence of Christie's working methods, as described by successive biographers, contradicts this claim.

Formula and plot devices

Almost all of Agatha Christie’s books are whodunits, focusing on the British middle and upper classes. Usually, the detective either stumbles across the murder or is called upon by an old acquaintance, who is somehow involved. Gradually, the detective interrogates each suspect, examines the scene of the crime and makes a note of each clue, so readers can analyze it and be allowed a fair chance of solving the mystery themselves. Then, about halfway through, or sometimes even during the final act, one of the suspects usually dies, often because they have inadvertently deduced the killer's identity and need silencing. In a few of her novels, including Death Comes as the End and And Then There Were None, there are multiple victims. Finally, the detective organises a meeting of all the suspects and slowly denounces the guilty party, exposing several unrelated secrets along the way, sometimes over the course of thirty or so pages. The murders are often extremely ingenious, involving some convoluted piece of deception. Christie’s stories are also known for their taut atmosphere and strong psychological suspense, developed from the deliberately slow pace of her prose.

Twice, the murderer surprisingly turns out to be the unreliable narrator of the story.

In five stories, Christie allows the murderer to escape justice (and in the case of the last three, implicitly almost approves of their crimes); these are The Witness for the Prosecution, The Man in the Brown Suit, Murder on the Orient Express, Curtain and The Unexpected Guest. After the dénouement of Taken at the Flood, her sleuth Poirot has the guilty party arrested for the lesser crime of manslaughter. (When Christie adapted Witness into a stage play, she lengthened the ending so that the murderer was also killed.) There are also numerous instances where the killer is not brought to justice in the legal sense but instead dies (death usually being presented as a more 'sympathetic' outcome), for example Death on the Nile, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Crooked House, Appointment with Death and The Hollow. In some cases this is with the collusion of the detective involved. Five Little Pigs, and arguably Ordeal by Innocence, end with the question of whether formal justice will be done unresolved.

Critical reception

Agatha Christie was revered as a master of suspense, plotting, and characterisation by most of her contemporaries and, even today, her stories have received glowing reviews in most literary circles. Fellow crime writer Anthony Berkeley Cox was an admitted fan of her work, once saying that nobody can write an Agatha Christie novel but the authoress herself.

However, she does have her detractors, most notably the American novelist Raymond Chandler, who criticised her in his essay, "The Simple Art of Murder", and the American literary critic Edmund Wilson, who was dismissive of Christie and the detective fiction genre generally in his New Yorker essay, "Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?".[31]

Others have criticized Christie on political grounds, particularly with respect to her conversations about and portrayals of Jews. Christopher Hitchens, in his autobiography, describes a dinner with Christie and her husband, Lord Mallowan, which became increasingly uncomfortable as the night wore on, and where "the anti-Jewish flavor of the talk was not to be ignored or overlooked."[32] Critic Johann Hari notes "In its ugliest moments, Christie’s conservatism crossed over into a contempt for Jews, who are so often associated with rationalist political philosophies and a ‘cosmopolitanism’ that is antithetical to the Burkean paradigm of the English village. There is a streak of anti-Semitism running through the pre-1950s novels which cannot be denied even by her admirers."[33]

Stereotyping

Christie occasionally inserted stereotyped descriptions of characters into her work, particularly before the end of the Second World War (when such attitudes were more commonly expressed publicly), and particularly in regard to Italians, Jews, and non-Europeans. For example, in the first editions of the collection The Mysterious Mr Quin (1930), in the short story "The Soul of the Croupier," she described "Hebraic men with hook-noses wearing rather flamboyant jewellery"; in later editions the passage was edited to describe "sallow men" wearing same. To contrast with the more stereotyped descriptions, Christie often characterised the "foreigners" in such a way as to make the reader understand and sympathise with them; this is particularly true of her Jewish characters, who are seldom actually criminals. (See, for example, the character of Oliver Manders in Three Act Tragedy.) [34]

Portrayals

Christie has been portrayed on a number of occasions in film and television.

Several biographical programs have been made, such as the 2004 BBC television program entitled Agatha Christie: A Life in Pictures, in which she is portrayed by Olivia Williams, Anna Massey, and Bonnie Wright.

Christie has also been portrayed fictionally. Some of these have explored and offered accounts of Christie's disappearance in 1926, including the 1979 film Agatha (with Vanessa Redgrave, where she sneaks away to plan revenge against her husband) and the Doctor Who episode "The Unicorn and the Wasp" (with Fenella Woolgar, her disappearance being the result of her suffering a temporary breakdown due to a brief psychic link being formed between her and an alien). Others, such as 1980 Hungarian film, Kojak Budapesten (not to be confused with the 1986 comedy by the same name) create their own scenarios involving Christie's criminal skill.[35] In the 1986 TV play, Murder by the Book, Christie herself (Peggy Ashcroft) murdered one of her fictional-turned-real characters, Poirot. The heroine of Liar-Soft's 2008 visual novel Shikkoku no Sharnoth ~What a beautiful tomorrow~, Mary Clarissa Christie, is based on the real-life Christie.

Christie has also been parodied on screen, such as in the film Murder by Indecision, which featured the character "Agatha Crispy".

List of works

See List of works by Agatha Christie

Other works based on Christie's books and plays

Plays adapted into novels by Charles Osborne

- 1998 Black Coffee (featuring Hercule Poirot, based on the 1930 play Black Coffee)

- 1999 The Unexpected Guest (featuring Miss Marple, based on the 1958 play The Unexpected Guest)

- 2000 Spider's Web (based on the 1954 play Spider's Web)

These three novels are now available in the collection Murder In Three Stages.

Plays adapted by other authors

- 1928 Alibi (dramatised by Michael Morton from the novel The Murder of Roger Ackroyd)

- 1936 Love from a Stranger (dramatised by Frank Vosper from the short story Philomel Cottage)

- 1939 Tea for Three (dramatised by Margery Vosper from the short story Accident)

- 1940 Peril at End House (dramatised from her novel by Arnold Ridley)

- 1949 Murder at the Vicarage (dramatised from the novel by Moie Charles and Barbara Toy)

- 1977 Murder at the Vicarage (dramatised from the novel by Leslie Darbon)

- 1981 Cards on the Table (dramatised from the novel by Leslie Darbon)

- 1993 Murder is Easy (dramatised from the novel by Clive Exton)

- 2005 And Then There Were None (dramatised from the novel by Kevin Elyot)

Movie adaptations

| Year | Title | Story Based On | Other Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1928 | "The Passing Of Mr. Quin" | The Coming of Mr. Quin | First Christie film adaptation. |

| 1929 | "Die Abenteurer G.m.b.H." | The Secret Adversary | First Christie foreign film adaptation. German adaptation of The Secret Adversary |

| 1931 | "Alibi" | The stage play Alibi and the novel The Murder of Roger Ackroyd | First Christie film adaptation to feature Hercule Poirot. |

| 1931 | "Black Coffee" | Black Coffee | |

| 1932 | "Le Coffret de Laque" | Black Coffee | French adaptation of Black Coffee. |

| 1934 | "Lord Edgware Dies" | Lord Edgware Dies | |

| 1937 | "Love from a Stranger" | The stage play Love from a Stranger and the short story Philomel Cottage | Released in the US as A Night of Terror. |

| 1945 | "And Then There Were None" | The stage play And Then There Were None and the novel And Then There Were None | First Christie film adaptation of And Then There Were None. |

| 1947 | "Love from a Stranger" | The stage play Love from a Stranger and the short story Philomel Cottage | Released in the UK as A Stranger Walked In. |

| 1957 | "Witness for the Prosecution" | The stage play Witness for the Prosecution and the short story The Witness for the Prosecution | |

| 1960 | "The Spider's Web" | Spider's Web | |

| 1961 | "Murder, She Said" | 4.50 From Paddington | First Christie film adaptation to feature Miss Marple. |

| 1963 | "Murder at the Gallop" | After the Funeral | |

| 1964 | "Murder Most Foul" | Mrs. McGinty's Dead | |

| 1964 | "Murder Ahoy!" | None | An original movie not based on any book, although it borrows some elements of They Do It With Mirrors. |

| 1965 | "Gumnaam" | And Then There Were None | Uncredited adaptation of And Then There Were None. |

| 1965 | "Ten Little Indians" | The stage play And Then There Were None and the novel And Then There Were None | |

| 1965 | "The Alphabet Murders" | The A.B.C. Murders | |

| 1972 | "Endless Night" | Endless Night | |

| 1974 | "Murder on the Orient Express" | Murder on the Orient Express | |

| 1974 | "And Then There Were None" | The stage play And Then There Were None and the novel And Then There Were None | Released in the US as Ten Little Indians. |

| 1978 | "Death on the Nile" | The stage play Murder on the Nile and the novel Death on the Nile | |

| 1980 | "The Mirror Crack'd" | The Mirror Crack'd from Side to Side | |

| 1982 | "Evil Under the Sun" | Evil Under the Sun | |

| 1985 | "Ordeal by Innocence" | Ordeal by Innocence | |

| 1987 | "Desyat Negrityat" | The stage play And Then There Were None and the novel And Then There Were None | Russian film adaptation of And Then There Were None. |

| 1988 | "Appointment With Death" | The stage play Appointment with Death and the novel Appointment with Death | |

| 1989 | "Ten Little Indians" | The stage play And Then There Were None and the novel And Then There Were None | |

| 1995 | "Innocent Lies" | Towards Zero | |

| 2005 | "Mon petit doigt m'a dit..." | By the Pricking of My Thumbs | French adaptation of By the Pricking of My Thumbs. |

| 2007 | "L'Heure zéro" | Towards Zero | French adaptation of Towards Zero. |

| 2008 | "Le crime est notre affaire" | 4.50 From Paddington | French adaptation of 4.50 From Paddington |

|

||||||||

Television adaptations

- 1938 Love from a Stranger (TV) (Based on the stage play of the same name from the short story Philomel Cottage)

- 1947 Love from a Stranger (TV)

- 1949 Ten Little Indians

- 1959 Ten Little Indians

- 1970 The Murder at the Vicarage

- 1980 Why Didn't They Ask Evans?

- 1982 Spider's Web (TV)

- 1982 The Seven Dials Mystery

- 1982 The Agatha Christie Hour

- 1982 Murder is Easy

- 1982 The Witness for the Prosecution

- 1983 The Secret Adversary

- 1983 Partners in Crime

- 1983 A Caribbean Mystery

- 1983 Sparkling Cyanide

- 1984 The Body in the Library

- 1985 Murder with Mirrors

- 1985 The Moving Finger

- 1985 A Murder is Announced

- 1985 A Pocket Full of Rye

- 1985 Thirteen at Dinner

- 1986 Dead Man's Folly

- 1986 Murder in Three Acts

- 1986 The Murder at the Vicarage

- 1987 Sleeping Murder

- 1987 At Bertram's Hotel

- 1987 Nemesis

- 1987 4.50 from Paddington

- 1989 The Man in the Brown Suit

- 1989 A Caribbean Mystery

- 1991 They Do It with Mirrors

- 1992 The Mirror Crack'd from Side to Side

- 1997 The Pale Horse

- 2001 Murder on the Orient Express

- 2003 Sparkling Cyanide'

- 2004 The Body in the Library

- 2004 The Murder at the Vicarage

- 2004 4.50 from Paddington

- 2005 A Murder is Announced

- 2005 Sleeping Murder

- 2006 The Moving Finger

- 2006 By the Pricking of My Thumbs

- 2006 The Sittaford Mystery

- 2007 Hercule Poirot's Christmas (A French film adaptation)

- 2007 Towards Zero

- 2007 Nemesis

- 2007 At Bertram's Hotel

- 2007 Ordeal by Innocence

- 2008 A Pocket Full of Rye

- 2008 Murder Is Easy

- 2008 Why Didn't They Ask Evans?

- 2008 They Do It with Mirrors

- 2009 The Mirror Crack'd from Side to Side

- 2009 The Secret of Chimneys

- 2010 The Blue Geranium

- 2010 The Pale Horse

Agatha Christie's Poirot television series

Episodes include:

- 1990 Peril at End House

- 1990 The Mysterious Affair at Styles

- 1992 The ABC Murders

- 1992 Death in the Clouds

- 1992 One, Two, Buckle My Shoe

- 1994 Hercule Poirot's Christmas

- 1995 Murder on the Links

- 1995 Hickory Dickory Dock

- 1996 Dumb Witness

- 2000 The Murder of Roger Ackroyd

- 2000 Lord Edgware Dies

- 2001 Evil Under the Sun

- 2001 Murder in Mesopotamia

- 2004 Five Little Pigs

- 2004 Death on the Nile

- 2004 Sad Cypress

- 2004 The Hollow

- 2005 The Mystery of the Blue Train

- 2005 Cards on the Table

- 2005 After the Funeral

- 2006 Taken at the Flood

- 2008 Mrs. McGinty's Dead

- 2008 Cat Among the Pigeons

- 2008 Third Girl

- 2008 Appointment with Death

- 2009 The Clocks

- 2009 Three Act Tragedy

- 2010 Hallowe'en Party

- 2010 Murder on the Orient Express

Graphic novels

Euro Comics India began issuing a series of graphic novel adaptations of Christie's work in 2007.

- 2007 The Murder on the Links Adapted by François Rivière, Illustrated by Marc Piskic

- 2007 Murder on the Orient Express Adapted by François Rivière, Illustrated by Solidor (Jean-François Miniac).

- 2007 Death on the Nile Adapted by Francois Riviere, Illustrated by Solidor (Jean-François Miniac)

- 2007 The Secret of Chimneys Adapted by François Rivière, Illustrated by Laurence Suhner

- 2007 The Murder of Roger Ackroyd Adapted and illustrated by Bruno Lachard

- 2007 The Mystery of the Blue Train Adapted and illustrated by Marc Piskic

- 2007 The Man in the Brown Suit Adapted and illustrated by Alain Paillou

- 2007 The Big Four Adapted by Hichot and illustrated by Bairi

- 2007 The Secret Adversary Adapted by François Rivière and illustrated by Frank Leclercq

- 2007 The Murder at the Vicarage Adapted and illustrated by "Norma"

- 2007 Murder in Mesopotamia Adapted by François Rivière and illustrated by Chandre

- 2007 And Then There Were None Adapted by François Rivière and illustrated by Frank Leclercq

- 2007 Endless Night Adapted by Francois Rivière and illustrated by Frank Leclercq

- 2008 Ordeal by Innocence Adapted and illustrated by Chandre

- 2008 Hallowe'en Party Adapted and illustrated by Chandre

HarperCollins independently began issuing this series also in 2007.

In addition to the titles issued the following titles are also planned for release:

- 2008 Peril at End House Adapted by Thierry Jollet and illustrated by Didier Quella-Guyot

- 2009 Dumb Witness Adapted and illustrated by "Marek"

Video games

- 1988 The Scoop (published by Spinnaker Software and Telarium) (PC)

- 2005 Agatha Christie: And Then There Were None (PC and Wii in 2008).

- 2006 Agatha Christie: Murder on the Orient Express (PC and Wii in 2009)

- 2007 Agathe Christie: Death on the Nile (I-Spy" hidden-object game) (PC)

- 2007 Agatha Christie: Evil Under the Sun (PC and Wii in 2008)

- 2008 Agatha Christie: Peril at End House (I-Spy" hidden-object game)

- 2009 Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders (DS)

- 2009 Agatha Christie: Dead Man's Folly (I-Spy" hidden-object game)(PC)

- 2010 Agatha Christie 4:50 from Paddington (I-Spy" hidden-object game)(PC)

Unpublished material

- Snow Upon the Desert (romantic novel)

- Personal Call (supernatural radio play, featuring Inspector Narracott who also appeared in The Sittaford Mystery; a recording is in the British Library Sound Archive)

- The Woman and the Kenite (horror: an Italian translation, allegedly transcribed from an Italian magazine of the 1920s, is available on the internet: La moglie del Kenita).

- Butter In a Lordly Dish (horror/detective radio play, adapted from The Woman and the Kenite)

- Being So Very Wilful (romantic)

- Two previously unpublished Poirot short stories, The Capture of Cerberus and The Incident of the Dog's Ball—both variants of published works—were included in The Secret Notebooks of Agatha Christie by John Curran, a study of Christie's plotwork published in 2009. (ISBN 0007310560)

Animation

In 2004 the Japanese broadcasting company Nippon Hōsō Kyōkai turned Poirot and Marple into animated characters in the anime series Agatha Christie's Great Detectives Poirot and Marple, introducing Mabel West (daughter of Miss Marple's mystery-writer nephew Raymond West, a canonical Christie character) and her duck Oliver as new characters.

See also

- Agatha Christie's Final Mystery Radio Documentary on RTE Radio One, Ireland about how Dubliner John Curran found a missing Poirot story at Greenway House

- Tropes in Agatha Christie's novels

- Agatha Christie: A Life in Pictures (Her life story in a 2004 BBC drama)

- Abney Hall (home to her brother-in-law; several books use Abney as their setting)

- Greenway Estate (Christie's former home in Devon. The grounds are now in the possession of the National Trust and open to the public)

- Agatha Christie indult (a non-denominational request to which Christie was signatory seeking permission for the occasional use of the Tridentine (Latin) mass in England and Wales)

Notes

- ↑ Flemming, Michael (February 15, 2000). "Agatha Christie gets a clue for filmmakers". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117776459.html?categoryid=3&cs=1. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Statistics on whole Index Translationum database". UNESCO. http://databases.unesco.org/xtrans/stat/xTransStat.a?VL1=A&top=50&lg=0. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ↑ Guinness Book of World Records p.210. Sterling Pub. Co., 1976

- ↑ "Chorion". Chorion. http://www.chorion.co.uk/. Retrieved 2010-03-09.

- ↑ Burton Frierson (2009-11-10). "Lost Agatha Christie story to be published". Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/lifestyleMolt/idUSTRE5A95OG20091110. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ↑ Morgan, Janet. Agatha Christie, A Biography. (Page 2) Collins, 1984 ISBN 0-00-216330-6

- ↑ Wagoner, Mary S. Agatha Christie. (Page 26) Twayne Publishers, 1986 ISBN 0805769366, 9780805769364

- ↑ Brief Biography of Agatha Christie Christie Bio

- ↑ Christie, p. 230

- ↑ Christie, pp. 215, 237

- ↑ "MRS. CHRISTIE FOUND IN A YORKSHIRE SPA; Missing Novelist, Under an Assumed Name, Was Staying at a Hotel There. CLUE A NEWSPAPER PICTURE Mystery Writer Is Victim of Loss of Memory, Her Husband Declares. MRS. CHRISTIE FOUND IN A YORKSHIRE SPA". New York Times. 1926-12-15. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F60C17FE3C591B7A93C7A81789D95F428285F9&scp=4&sq=Agatha%20Christie%20Disappearance&st=cse. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ↑ The Harrogate Hydropathic hotel, nowadays the Old Swan Hotel, was also known as the Swan Hydro, because of its location on Swan Road, on the site of an earlier Old Swan Hotel. A Brief History of Harrogate

- ↑ Adams, Cecil, Why did mystery writer Agatha Christie mysteriously disappear? The Chicago Reader, 4/2/82. [1] Accessed 5/19/08.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Thompson, Laura. Agatha Christie: An English Mystery. London: Headline Review. 2008. ISBN 978-0-7553-1488-1.

- ↑ jbottero; "Agatha Christie's Hotel Pera Palace" http://virtualglobetrotting.com/map/51232/ 2008-06-05 23:08:11

- ↑ Agatha Christie: A Reader's Companion –Vanessa Wagstaff and Stephen Poole, Aurum Press Ltd. 2004. Page 14. ISBN 1845130154.

- ↑ "Thallium poisoning in fact and fiction" http://www.pharmj.com/pdf/comment/pj_20061125_onlooker.pdf

- ↑ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 40669, p. 11, 30 December 1955. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ↑ "Biography: Agatha Christie" Retrieved 22 February 2009; http://www.illiterarty.com/authors/biography-agatha-christie

- ↑ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 45262, p. 7, 31 December 1970. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ↑ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 44600, p. 6300, 31 May 1968. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ↑ Kingston, Anne. “The ultimate whodunit,” Maclean’s. 2 April 2009. (Retrieved 2009-08-28.)

- ↑ Boswell, Randy. “Study finds possible dementia for Agatha Christie,” The Ottawa Citizen. 6 April 2009. (Retrieved 2009-08-28.)

- ↑ Devlin, Kate. “Agatha Christie ‘had Alzheimer’s disease when she wrote final novels,’” The Telegraph. 4 April 2009. (Retrieved 2009-08-28.)

- ↑ Flood, Alison. “Study claims Agatha Christie had Alzheimer’s,” The Guardian. 3 April 2009. (Retrieved 2009-08-28.)

- ↑ "Agatha Christie suffered from Alzheimer's". Toronto: Prokerala News. 17 December 2009. http://www.prokerala.com/news/articles/a100939.html. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- ↑ "Deaths England and Wales 1984–2006". Findmypast.com. http://www.findmypast.com/BirthsMarriagesDeaths.jsp. Retrieved 2010-03-09.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Mills, Selina (2008-09-15). "BBC:Dusty clues to Christie unearthed". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/today/newsid_7612000/7612534.stm. Retrieved 2010-03-09.

- ↑ "Agatha Christie – Her Detectives and Other Characters" Retrieved 22 February 2009 http://www.christiemystery.co.uk/detectives.html

- ↑ Aldiss, Brian. "BBC Radio 4 –Factual –Desert Island Discs -Brian Aldiss". bbc.com. http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/factual/desertislanddiscs_20070128.shtml. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ↑ Wilson, Edmund. “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?” The New Yorker. January 20, 1945.

- ↑ Christopher Hitchens. Hitch-22. Hachette.. Hitchens goes on to critique Christie's writing style as well, opining "There must be some connection between the general nullity of Christie's prose and the tendency of her detectives to take Jewishness as a symptom of crime."

- ↑ Johann Hari (3 Oct 2003). ""Agatha Christie - radical conservative thinker"". http://www.johannhari.com/2003/10/04/agatha-christie-radical-conservative-thinker.. Hari gives several examples. "‘The Mysterious Mr Quinn’ has an ugly passage about "men of Hebraic extraction, sallow men with hooked noses, wearing flamboyant jewellery." ‘Peril At End House’ has a character referred to as "the long-nosed Mr Lazarus", of whom somebody says, "he’s a Jew, of course, but a frightfully decent one." Against this, it is worth pointing out that her novel ‘Giant’s Bread’ (written under the pseudonym of Mary Westmacott) features an extremely sympathetic portrait of the Levinnes, a Jewish family who suffer from anti-Semitism in England. Christie’s hostility to Jews was, I suspect, more political than personal (and no less reprehensible for that)."

- ↑ Pendergast, Bruce (2004). Everyman's Guide to the Mysteries of Agatha Christie. Victoria, BC, Canada: Trafford. p. 399. ISBN 1412023041.

- ↑ "Kojak Budapesten" 1990. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0081006/plotsummary

References

- Christie, Agatha (1977). Agatha Christie: An Autobiography. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. ISBN 0396075169.

Further reading

Articles

- Knepper, Marty S. (Summer 2005). "The Curtain Falls : Agatha Christie's Last Novels". CLUES : A Journal of Detection 23 (4): 69 –84. doi:10.3200/CLUS.23.4.69-84.

- Mann, Jessica (2007-09-20). "Taking liberties with Agatha Christie (review of Laura Thompson's Agatha Christie: An English Mystery)". Daily Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/non_fictionreviews/3668017/Taking-liberties-with-Agatha-Christie.html.

- Kerridge, Jake (2007-10-11). "The crimes of Agatha Christie (print edition of 6 October 2007: She made murder a parlour game) (review of Laura Thompson's Agatha Christie: An English Mystery)". The Daily Telegraph (Review). p. 24. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/non_fictionreviews/3668468/The-crimes-of-Agatha-Christie.html.

- Agatha Christie's holiday home |url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/4785905/Agatha-Christies-holiday-home-opens-to-the-public.html|

Books

- Barnard, Robert (1980). A Talent to Deceive –An Appreciation of Agatha Christie. London: Collins. ISBN 0002161907. Reprinted as New York: Mysterious Press, 1987.

- Thompson, Laura (2007). Agatha Christie : An English Mystery. London: Headline Review. ISBN 0755314875.

External links

- Official Agatha Christie site

- Agatha Christie at the Internet Movie Database

- Agatha Christie at Find a Grave

- Works by Agatha Christie at Project Gutenberg

- Dutch Agatha Christie collection

- AgathaChristie.net Unofficial Christie website

- Agatha Christie profile and articles at "The Guardian"

- Agatha Christie profile on PBS.ORG

- "Biography of an Author"

- Agatha Christie Festival in Torquay

- Agatha Christie’s style and methods, the plot devices that she uses to trick the reader

- Newly discovered audio tapes of Agatha Christie talking about the origins of Miss Marple online here

- Agatha Christie biography on Biogs.com

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||